Wellington[b] is the capital city of New Zealand. It is located at the south-western tip of the North Island, between Cook Strait and the Remutaka Range. Wellington is the third-largest city in New Zealand (second largest in the North Island),[c] and is the administrative centre of the Wellington Region. It is the world’s southernmost capital of a sovereign state.[16] Wellington features a temperate maritime climate, and is the world’s windiest city by average wind speed.[17]

Māori oral tradition tells that Kupe discovered and explored the region in about the 10th century. The area was initially settled by Māori iwi such as Rangitāne and Muaūpoko. The disruptions of the Musket Wars led to them being overwhelmed by northern iwi such as Te Āti Awa by the early 19th century.[18]

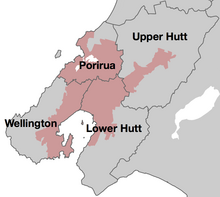

Wellington’s current form was originally designed by Captain William Mein Smith, the first Surveyor General for Edward Wakefield‘s New Zealand Company, in 1840.[19] Smith’s plan included a series of interconnected grid plans, expanding along valleys and lower hill slopes.[20] The Wellington urban area, which only includes urbanised areas within Wellington City, has a population of 214,200 as of June 2024.[9] The wider Wellington metropolitan area, including the cities of Lower Hutt, Porirua and Upper Hutt, has a population of 440,700 as of June 2024.[9] The city has served as New Zealand’s capital since 1865, a status that is not defined in legislation, but established by convention; the New Zealand Government and Parliament, the Supreme Court and most of the public service are based in the city.[21]

Wellington’s economy is primarily service-based, with an emphasis on finance, business services, government, and the film industry. It is the centre of New Zealand’s film and special effects industries, and increasingly a hub for information technology and innovation,[22] with two public research universities. Wellington is one of New Zealand’s chief seaports and serves both domestic and international shipping. The city is chiefly served by Wellington International Airport in Rongotai, the country’s third-busiest airport. Wellington’s transport network includes train and bus lines which reach as far as the Kāpiti Coast and the Wairarapa, and ferries connect the city to the South Island.

Often referred to as New Zealand’s cultural capital, the culture of Wellington is a diverse and often youth-driven one which has wielded influence across Oceania.[23][24][25] One of the world’s most liveable cities, the 2021 Global Livability Ranking tied Wellington with Tokyo as fourth in the world.[26] From 2017 to 2018, Deutsche Bank ranked it first in the world for both livability and non-pollution.[27][28] Cultural precincts such as Cuba Street and Newtown are renowned for creative innovation, “op shops“, historic character, and food. Wellington is a leading financial centre in the Asia-Pacific region, being ranked 46th in the world by the Global Financial Centres Index for 2024. The global city has grown from a bustling Māori settlement, to a colonial outpost, and from there to an Australasian capital that has experienced a “remarkable creative resurgence”.[29][30][31][32]

Toponymy

[edit]

Wellington takes its name from Arthur Wellesley, the first Duke of Wellington and victor of the Battle of Waterloo (1815): his title comes from the town of Wellington in the English county of Somerset. It was named in November 1840 by the original settlers of the New Zealand Company on the suggestion of the directors of the same, in recognition of the Duke’s strong support for the company’s principles of colonisation and his “strenuous and successful defence against its enemies of the measure for colonising South Australia”. One of the founders of the settlement, Edward Jerningham Wakefield, reported that the settlers “took up the views of the directors with great cordiality and the new name was at once adopted”.[33]

In the Māori language, Wellington has three names:

- Te Whanganui-a-Tara, meaning “the great harbour of Tara”, refers to Wellington Harbour.[34] The primary settlement of Wellington is said to have been led by Tara, the son of Whatonga, a chief from the Māhia Peninsula, who told his son to travel south, to find more fertile lands to settle.[35]

- Pōneke, commonly held to be a phonetic Māori transliteration of “Port Nick”, short for “Port Nicholson“.[36] An alternatively suggested etymology for Pōneke is that it comes from a shortening of the phrase Pō Nekeneke, meaning “journey into the night”, referring to the exodus of Te Āti Awa from the Wellington area after they were displaced by the first European settlers.[37][38][39] However, the name Pōneke was already in use by February 1842,[40] earlier than the displacement is said to have happened. The city’s central marae, the community supporting it and its kapa haka group have the pseudo-tribal name of Ngāti Pōneke.[41]

- Te Upoko-o-te-Ika-a-Māui, meaning “The Head of the Fish of Māui” (often shortened to Te Upoko-o-te-Ika), a traditional name for the southernmost part of the North Island, deriving from the legend of the fishing up of the island by the demi-god Māui.

The legendary Māori explorer Kupe, a chief from Hawaiki (the homeland of Polynesian explorers, of unconfirmed geographical location, not to be confused with Hawaii), was said to have stayed in the harbour prior to 1000 CE.[35] Here, it is said he had a notable impact on the area, with local mythology stating he named the two islands in the harbour after his daughters, Matiu (Somes Island), and Mākaro (Ward Island).[42]

In New Zealand Sign Language, the name is signed by raising the index, middle, and ring fingers of one hand, palm forward, to form a “W”, and shaking it slightly from side to side twice.[43]

The city’s location close to the mouth of the narrow Cook Strait leaves it vulnerable to strong gales, leading to the nickname of “Windy Wellington”.[44]

History

[edit]

Māori settlement

[edit]

Legends recount that Kupe discovered and explored the region in about the 10th century. Before European colonisation, the area in which the city of Wellington would eventually be founded was seasonally inhabited by indigenous Māori. The earliest date with hard evidence for human activity in New Zealand is about 1280.[45]

Wellington and its environs have been occupied by various Māori groups from the 12th century. The legendary Polynesian explorer Kupe, a chief from Hawaiki (the homeland of Polynesian explorers, of unconfirmed geographical location, not to be confused with Hawaii), was said to have stayed in the harbour from c. 925.[35][46] A later Māori explorer, Whatonga, named the harbour Te Whanganui-a-Tara after his son Tara.[47] Before the 1820s, most of the inhabitants of the Wellington region were Whatonga’s descendants.[48]

At about 1820, the people living there were Ngāti Ira and other groups who traced their descent from the explorer Whatonga, including Rangitāne and Muaūpoko.[18] However, these groups were eventually forced out of Te Whanganui-a-Tara by a series of migrations by other iwi (Māori tribes) from the north.[18] The migrating groups were Ngāti Toa, which came from Kāwhia, Ngāti Rangatahi, from near Taumarunui, and Te Ātiawa, Ngāti Tama, Ngāti Mutunga, Taranaki and Ngāti Ruanui from Taranaki. Ngāti Mutunga later moved on to the Chatham Islands. The Waitangi Tribunal has found that at the time of the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840, Te Ātiawa, Taranaki, Ngāti Ruanui, Ngāti Tama, and Ngāti Toa held mana whenua interests in the area, through conquest and occupation.[18]

Early European settlement

[edit]

Steps towards European settlement in the area began in 1839, when Colonel William Wakefield arrived to purchase land for the New Zealand Company to sell to prospective British settlers.[18] Prior to this time, the Māori inhabitants had had contact with Pākehā whalers and traders.[49]

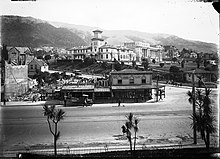

European settlement began with the arrival of an advance party of the New Zealand Company on the ship Tory on 20 September 1839, followed by 150 settlers on the Aurora on 22 January 1840. Thus, the Wellington settlement preceded the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi (on 6 February 1840). The 1840 settlers constructed their first homes at Petone (which they called Britannia for a time) on the flat area at the mouth of the Hutt River. Within months that area proved swampy and flood-prone, and most of the newcomers transplanted their settlement across Wellington Harbour to Thorndon in the present-day site of Wellington city.[50]

National capital

[edit]

See also: Capital of New Zealand

Wellington was declared a city in 1840, and was chosen to be the capital city of New Zealand in 1865.[21]

Wellington became the capital city in place of Auckland, which William Hobson had made the capital in 1841. The New Zealand Parliament had first met in Wellington on 7 July 1862, on a temporary basis; in November 1863, the Prime Minister of New Zealand, Alfred Domett, placed a resolution before Parliament in Auckland that “… it has become necessary that the seat of government … should be transferred to some suitable locality in Cook Strait [region].” There had been some concerns that the more populous South Island (where the goldfields were located) would choose to form a separate colony in the British Empire. Several commissioners (delegates) invited from Australia, chosen for their neutral status, declared that the city was a suitable location because of its central location in New Zealand and its good harbour; it was believed that the whole Royal Navy fleet could fit into the harbour.[51] Wellington’s status as the capital is a result of constitutional convention rather than statute.[21]

Wellington is New Zealand’s political centre, housing the nation’s major government institutions. The New Zealand Parliament relocated to the new capital city, having spent the first ten years of its existence in Auckland.[52] A session of parliament officially met in the capital for the first time on 26 July 1865. At that time, the population of Wellington was just 4,900.[53]

The Government Buildings were constructed at Lambton Quay in 1876. The site housed the original government departments in New Zealand. The public service rapidly expanded beyond the capacity of the building, with the first department leaving shortly after it was opened; by 1975 only the Education Department remained, and by 1990 the building was empty. The capital city is also the location of the highest court, the Supreme Court of New Zealand, and the historic former High Court building (opened 1881) has been enlarged and restored for its use. The Governor-General’s residence, Government House (the current building completed in 1910) is situated in Newtown, opposite the Basin Reserve. Premier House (built in 1843 for Wellington’s first mayor, George Hunter), the official residence of the prime minister, is in Thorndon on Tinakori Road.

Over six months in 1939 and 1940, Wellington hosted the New Zealand Centennial Exhibition, celebrating a century since the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi. Held on 55 acres of land at Rongotai, it featured three exhibition courts, grand Art Deco-style edifices and a hugely popular three-acre amusement park. Wellington attracted more than 2.5 million visitors at a time when New Zealand’s population was 1.6 million.[54]

Geography

[edit]

Wellington is at the south-western tip of the North Island on Cook Strait, separating the North and South Islands. On a clear day, the snowcapped Kaikōura Ranges are visible to the south across the strait. To the north stretch the golden beaches of the Kāpiti Coast. On the east, the Remutaka Range divides Wellington from the broad plains of the Wairarapa, a wine region of national notability.

With a latitude of 41° 17′ South, Wellington is the southernmost capital city in the world.[55] Wellington ties with Canberra, Australia, as the most remote capital city, 2,326 km (1,445 mi) apart from each other.

Wellington is more densely populated than most other cities in New Zealand due to the restricted amount of land that is available between its harbour and the surrounding hills. It has very few open areas in which to expand, and this has brought about the development of the suburban towns. Because of its location in the Roaring Forties and its exposure to the winds blowing through Cook Strait, Wellington is the world’s windiest city, with an average wind speed of 27 km/h (17 mph).[56]

Wellington’s scenic natural harbour and green hillsides adorned with tiered suburbs of colonial villas are popular with tourists. The central business district (CBD) is close to Lambton Harbour, an arm of Wellington Harbour, which lies along an active geological fault, clearly evident on its straight western shore. The land to the west of this rises abruptly, meaning that many suburbs sit high above the centre of the city. There is a network of bush walks and reserves maintained by the Wellington City Council and local volunteers. These include Otari-Wilton’s Bush, dedicated to the protection and propagation of native plants. The Wellington region has 500 square kilometres (190 sq mi) of regional parks and forests. In the east is the Miramar Peninsula, connected to the rest of the city by a low-lying isthmus at Rongotai, the site of Wellington International Airport. Industry has developed mainly in the Hutt Valley, where there are food-processing plants, engineering industries, vehicle assembly and oil refineries.[57]

The narrow entrance to the harbour is to the east of the Miramar Peninsula, and contains the dangerous shallows of Barrett Reef, where many ships have been wrecked (notably the inter-island ferry TEV Wahine in 1968).[58] The harbour has three islands: Matiu/Somes Island, Makaro/Ward Island and Mokopuna Island. Only Matiu/Somes Island is large enough for habitation. It has been used as a quarantine station for people and animals, and was an internment camp during World War I and World War II. It is a conservation island, providing refuge for endangered species, much like Kapiti Island farther up the coast. There is access during daylight hours by the Dominion Post Ferry.

Wellington is primarily surrounded by water, but some of the nearby locations are listed below.

Panorama of Wellington and surrounds

Geology

[edit]

Wellington suffered serious damage in a series of earthquakes in 1848[59] and from another earthquake in 1855. The 1855 Wairarapa earthquake occurred on the Wairarapa Fault to the north and east of Wellington. It was probably the most powerful earthquake in recorded New Zealand history,[60] with an estimated magnitude of at least 8.2 on the Moment magnitude scale. It caused vertical movements of two to three metres over a large area, including raising land out of the harbour and turning it into a tidal swamp. Much of this land was subsequently reclaimed and is now part of the central business district. For this reason, the street named Lambton Quay is 100 to 200 metres (325 to 650 ft) from the harbour – plaques set into the footpath mark the shoreline in 1840, indicating the extent of reclamation. The 1942 Wairarapa earthquakes caused considerable damage in Wellington.

The area has high seismic activity even by New Zealand standards, with a major fault, the Wellington Fault, running through the centre of the city and several others nearby. Several hundred minor faults lines have been identified within the urban area. Inhabitants, particularly in high-rise buildings, typically notice several earthquakes every year. For many years after the 1855 earthquake, the majority of buildings were made entirely from wood. The 1996-restored Government Buildings[61] near Parliament is the largest wooden building in the Southern Hemisphere. While masonry and structural steel have subsequently been used in building construction, especially for office buildings, timber framing remains the primary structural component of almost all residential construction. Residents place their confidence in good building regulations, which became more stringent in the 20th century. Since the Canterbury earthquakes of 2010 and 2011, earthquake readiness has become even more of an issue, with buildings declared by Wellington City Council to be earthquake-prone,[62][63] and the costs of meeting new standards.[64][65]

Every five years, a year-long slow quake occurs beneath Wellington, stretching from Kapiti to the Marlborough Sounds. It was first measured in 2003, and reappeared in 2008 and 2013.[66] It releases as much energy as a magnitude 7 quake, but as it happens slowly, there is no damage.[67]

During July and August 2013 there were many earthquakes, mostly in Cook Strait near Seddon. The sequence started at 5:09 pm on Sunday 21 July 2013 when the magnitude 6.5 Seddon earthquake hit the city, but no tsunami report was confirmed nor any major damage.[68] At 2:31 pm on Friday 16 August 2013 the Lake Grassmere earthquake struck, this time magnitude 6.6, but again no major damage occurred, though many buildings were evacuated.[69] On Monday 20 January 2014 at 3:52 pm a rolling 6.2 magnitude earthquake struck the lower North Island 15 km east of Eketāhuna and was felt in Wellington, but little damage was reported initially, except at Wellington Airport where one of the two giant eagle sculptures commemorating The Hobbit became detached from the ceiling.[70][71]

At two minutes after midnight on Monday 14 November 2016, the 7.8 magnitude Kaikōura earthquake, which was centred between Culverden and Kaikōura in the South Island, caused the Wellington CBD, Victoria University of Wellington, and the Wellington suburban rail network to be largely closed for the day to allow inspections. The earthquake damaged a considerable number of buildings, with 65% of the damage being in Wellington. Subsequently, a number of recent buildings were demolished rather than being rebuilt, often a decision made by the insurer. Two of the buildings demolished were about eleven years old – the seven-storey NZDF headquarters[72][73] and Statistics House at Centreport on the waterfront.[74] The docks were closed for several weeks after the earthquake.[75]

Relief

[edit]

Steep landforms shape and constrain much of Wellington city. Notable hills in and around Wellington include:

- Mount Victoria – 196 m. Mt Vic is a popular walk for tourists and Wellingtonians alike, as from the summit one can see most of Wellington. There are numerous mountain bike and walking tracks on the hill.

- Mount Albert[76] – 178 m

- Mount Cook

- Mount Alfred (west of Evans Bay)[77] – 122 m

- Mount Kaukau – 445 m. Site of Wellington’s main television transmitter.

- Mount Crawford[78]

- Brooklyn Hill – 299 m

- Wrights Hill

- Mākara Peak – summit (412 m) is within the 250 ha Makara Peak Mountain Bike Park that includes 45 km of trails[79]

- Te Ahumairangi (Tinakori) Hill

Climate

[edit]

Averaging 2,055 hours of sunshine per year, the climate of Wellington is temperate marine, (Köppen: Cfb, Trewartha: Cflk), generally moderate all year round with mild summers and cool to mild winters, and rarely sees temperatures above 28 °C (82 °F) or below 4 °C (39 °F). The hottest recorded temperature in the city is 31.1 °C (88 °F) recorded on 20 February 1896[citation needed], while −1.9 °C (29 °F) is the coldest.[80] The city is notorious for its southerly blasts in winter, which may make the temperature feel much colder. It is generally very windy all year round with high rainfall; average annual rainfall is 1,250 mm (49 in), June and July being the wettest months. Frosts are quite common in the hill suburbs and the Hutt Valley between May and September. Snow is very rare at low altitudes, although snow fell on the city and many other parts of the Wellington region during separate events on 25 July 2011 and 15 August 2011.[81][82] Snow at higher altitudes is more common, with light flurries recorded in higher suburbs every few years.[83]

On 29 January 2019, the suburb of Kelburn (instruments near the old Metservice building in the Wellington Botanic Garden) reached 30.3 °C (87 °F), the highest temperature since records began in 1927.[84]

| showClimate data for Wellington International Airport (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1962–present) |

|---|

Demographics

[edit]

Wellington City covers 289.91 km2 (111.93 sq mi)[90] and had an estimated population of 215,300 as of June 2024,[9] with a population density of 743 people per km2. This comprises 214,200 people in the Wellington urban area and 1,100 people in the surrounding rural areas.[9]

Wellington City had a population of 202,689 in the 2023 New Zealand census, a decrease of 48 people (−0.0%) since the 2018 census, and an increase of 11,733 people (6.1%) since the 2013 census. There were 97,641 males, 102,372 females and 2,673 people of other genders in 77,835 dwellings.[93] 9.0% of people identified as LGBTIQ+. The median age was 34.9 years (compared with 38.1 years nationally). There were 29,142 people (14.4%) aged under 15 years, 55,080 (27.2%) aged 15 to 29, 94,806 (46.8%) aged 30 to 64, and 23,664 (11.7%) aged 65 or older.[92]

People could identify as more than one ethnicity. The results were 72.1% European (Pākehā); 9.8% Māori; 5.7% Pasifika; 20.4% Asian; 3.6% Middle Eastern, Latin American and African New Zealanders (MELAA); and 2.1% other, which includes people giving their ethnicity as “New Zealander”. English was spoken by 96.3%, Māori language by 2.7%, Samoan by 1.7% and other languages by 23.4%. No language could be spoken by 1.6% (e.g. too young to talk). New Zealand Sign Language was known by 0.6%. The percentage of people born overseas was 34.4, compared with 28.8% nationally.

Religious affiliations were 26.9% Christian, 3.8% Hindu, 1.8% Islam, 0.4% Māori religious beliefs, 1.7% Buddhist, 0.5% New Age, 0.3% Jewish, and 1.9% other religions. People who answered that they had no religion were 57.7%, and 5.2% of people did not answer the census question.

Of those at least 15 years old, 62,484 (36.0%) people had a bachelor’s or higher degree, 66,657 (38.4%) had a post-high school certificate or diploma, and 24,339 (14.0%) people exclusively held high school qualifications. The median income was $55,500, compared with $41,500 nationally. 40,872 people (23.6%) earned over $100,000 compared to 12.1% nationally. The employment status of those at least 15 was that 102,369 (59.0%) people were employed full-time, 24,201 (13.9%) were part-time, and 5,283 (3.0%) were unemployed.[92]

| Name | Area (km2) | Population | Density (per km2) | Dwellings | Median age | Median income |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Takapū/Northern General Ward | 102.88 | 50,466 | 491 | 17,598 | 36.6 years | $55,900[94] |

| Wharangi/Onslow-Western General Ward | 125.82 | 42,585 | 338 | 15,858 | 39.1 years | $64,300[95] |

| Pukehīnau/Lambton General Ward | 9.86 | 40,134 | 4,070 | 17,679 | 29.1 years | $49,700[96] |

| Motukairangi/Eastern General Ward | 16.20 | 36,843 | 2,274 | 14,235 | 37.9 years | $54,500[97] |

| Paekawakawa/Southern General Ward | 32,658 | 929 | 12,465 | 35.0 years | $54,200[98] | |

| New Zealand | 38.1 years | $41,500 |

Quality of living

[edit]

Wellington ranks 12th in the world for quality of living, according to a 2023 study by consulting company Mercer. Of cities in the Asia–Pacific region, Wellington ranked third behind Auckland and Sydney.[99]

In 2024, Wellington was ranked as a highly affordable city in terms of cost of living, coming in at 145th out of 226 cities in the Mercer worldwide Cost of Living Survey.[100]

In 2019, Mercer ranked cities on personal safety, including internal stability, crime levels, law enforcement, limitations on personal freedom, relationships with other countries and freedom of the press. Wellington shared ninth place internationally with Auckland.[101]

Culture and identity

[edit]

In addition to governmental institutions, Wellington accommodates several of the nation’s largest and oldest cultural institutions, such as the National Archives, the National Library, New Zealand’s national museum, Te Papa and numerous theatres. It plays host to many artistic and cultural organisations, including the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra and Royal New Zealand Ballet. Its architectural attractions include the Old Government Buildings – one of the largest wooden buildings in the world – as well as the iconic Beehive, the executive wing of Parliament Buildings as well as internationally renowned Futuna Chapel. The city’s art scene includes many art galleries, including the national art collection at Toi Art at Te Papa.[102] Wellington also has many events such as CubaDupa, Wellington On a Plate, the Newtown Festival, Diwali Festival of Lights and Gardens Magic at the Botanical Gardens.[103][104][105]

| Ethnicity | 2006 census | 2013 census | 2018 census | 2023 census | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| European | 121,296 | 70.1 | 139,107 | 76.4 | 150,198 | 74.1 | 146,208 | 72.1 |

| Māori | 13,335 | 7.7 | 14,433 | 7.9 | 17,409 | 8.6 | 19,878 | 9.8 |

| Pacific peoples | 8,931 | 5.2 | 8,928 | 4.9 | 10,392 | 5.1 | 11,565 | 5.7 |

| Asian | 22,851 | 13.2 | 28,542 | 15.7 | 37,158 | 18.3 | 41,436 | 20.4 |

| Middle Eastern/Latin American/African | 3,615 | 2.1 | 4,494 | 2.5 | 6,135 | 3.0 | 7,356 | 3.6 |

| Other | 18,384 | 10.6 | 3,351 | 1.8 | 2,892 | 1.4 | 2,166 | 1.1 |

| Total people stated | 172,971 | 182,121 | 202,737 | 202,689 | ||||

| Not elsewhere included | 6,492 | 3.8 | 8,835 | 4.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

Urban area

[edit]

Wellington’s urban area covers 112.71 km2 (43.52 sq mi)[90] and had an estimated population of 214,200 as of June 2024,[9] with a population density of 1,900 people per km2.

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 2013 | 190,113 | — |

| 2018 | 201,792 | +1.20% |

| 2023 | 201,708 | −0.01% |

| Source: [107] | ||

The urban area had a population of 201,708 in the 2023 New Zealand census, a decrease of 84 people (−0.0%) since the 2018 census, and an increase of 11,595 people (6.1%) since the 2013 census. There were 97,143 males, 101,898 females and 2,667 people of other genders in 77,472 dwellings.[108] 9.0% of people identified as LGBTIQ+. The median age was 34.9 years (compared with 38.1 years nationally). There were 28,986 people (14.4%) aged under 15 years, 54,912 (27.2%) aged 15 to 29, 94,272 (46.7%) aged 30 to 64, and 23,541 (11.7%) aged 65 or older.[107]

People could identify as more than one ethnicity. The results were 72.0% European (Pākehā); 9.8% Māori; 5.7% Pasifika; 20.5% Asian; 3.6% Middle Eastern, Latin American and African New Zealanders (MELAA); and 2.1% other, which includes people giving their ethnicity as “New Zealander”. English was spoken by 96.3%, Māori language by 2.7%, Samoan by 1.8% and other languages by 23.5%. No language could be spoken by 1.7% (e.g. too young to talk). New Zealand Sign Language was known by 0.6%. The percentage of people born overseas was 34.4, compared with 28.8% nationally.

Religious affiliations were 26.9% Christian, 3.8% Hindu, 1.8% Islam, 0.4% Māori religious beliefs, 1.7% Buddhist, 0.5% New Age, 0.3% Jewish, and 1.9% other religions. People who answered that they had no religion were 57.6%, and 5.2% of people did not answer the census question.

Of those at least 15 years old, 62,259 (36.0%) people had a bachelor’s or higher degree, 66,273 (38.4%) had a post-high school certificate or diploma, and 24,219 (14.0%) people exclusively held high school qualifications. The median income was $55,400, compared with $41,500 nationally. 40,632 people (23.5%) earned over $100,000 compared to 12.1% nationally. The employment status of those at least 15 was that 101,892 (59.0%) people were employed full-time, 24,063 (13.9%) were part-time, and 5,268 (3.0%) were unemployed.[107]

Architecture

[edit]

Further information: List of tallest buildings in Wellington

Wellington showcases a variety of architectural styles from the past 150 years – 19th-century wooden cottages, such as the Italianate Katherine Mansfield Birthplace in Thorndon; streamlined Art Deco structures such as the old Wellington Free Ambulance headquarters, the Central Fire Station, Fountain Court Apartments, the City Gallery, and the former Post and Telegraph Building; and the curves and vibrant colours of post-modern architecture in the CBD.

The oldest building is the 1858 Nairn Street Cottage in Mount Cook.[109] The tallest building is the Majestic Centre on Willis Street at 116 metres high, the second-tallest being the structural expressionist Aon Centre (Wellington) at 103 metres.[110] Futuna Chapel in Karori is an iconic building designed by Māori architect John Scott and is architecturally considered one of the most significant New Zealand buildings of the 20th century.[111]

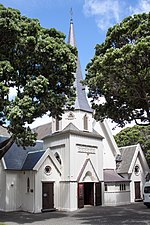

Old St Paul’s is an example of 19th-century Gothic Revival architecture adapted to colonial conditions and materials, as is St Mary of the Angels. Sacred Heart Cathedral is a Palladian Revival Basilica with the Portico of a Roman or Greek temple. The Museum of Wellington City & Sea in the Bond Store is in the Second French Empire style, and the Wellington Harbour Board Wharf Office Building is in a late English Classical style. There are several restored theatre buildings: the St James Theatre, the Opera House and the Embassy Theatre.

Te Ngākau Civic Square is surrounded by the Town Hall and council offices, the Michael Fowler Centre, the Wellington Central Library, the City-to-Sea Bridge, and the City Gallery.

As it is the capital city, there are many notable government buildings. The Executive Wing of New Zealand Parliament Buildings, on the corner of Lambton Quay and Molesworth Street, was constructed between 1969 and 1981 and is commonly referred to as the Beehive. Across the road is the largest wooden building in the Southern Hemisphere,[112] part of the old Government Buildings which now houses part of Victoria University of Wellington‘s Law Faculty.

A modernist building housing the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa lies on the waterfront, on Cable Street. It is strengthened using base isolation[113] – essentially seating the entire building on supports made from lead, steel and rubber that slow down the effect of an earthquake.

Other notable buildings include Wellington Town Hall, Wellington railway station, Dominion Museum (now Massey University), Aon Centre (Wellington), Wellington Regional Stadium, and Wellington Airport at Rongotai. Leading architects include Frederick Thatcher, Frederick de Jersey Clere, W. Gray Young, Bill Alington, Ian Athfield, Roger Walker.

Wellington contains many iconic sculptures and structures, such as the Bucket Fountain in Cuba Street and Invisible City by Anton Parsons on Lambton Quay. Kinetic sculptures have been commissioned, such as the Zephyrometer.[114] This 26-metre orange spike built for movement by artist Phil Price has been described as “tall, soaring and elegantly simple”, which “reflects the swaying of the yacht masts in the Evans Bay Marina behind it” and “moves like the needle on the dial of a nautical instrument, measuring the speed of the sea or wind or vessel.”[115]

Wellington has many different architectural styles, such as classic Painted Ladies in Mount Victoria, Newtown and Oriental Bay, Wooden Art Deco houses spread throughout (especially further north in the Hutt Valley), the classic masonry buildings in Cuba Street, state houses particularly in the Hutt and Wellington’s southern suburbs, railway houses in Ngaio and other railway-side suburbs, large modern buildings in the city centre (such as the distinctive skyscraper called the Majestic Centre) and grand Victorian buildings common in the inner city as well.

Housing and real estate

[edit]

See also: Housing in New Zealand

House prices

[edit]

Historic

[edit]

Wellington experienced a real estate boom in the early 2000s and the effects of the international property bust at the start of 2007. In 2005, the market was described as “robust”.[116] By 2008, property values had declined by about 9.3% over a 12-month period, according to one estimate. More expensive properties declined more steeply, sometimes by as much as 20%.[117] “From 2004 to early 2007, rental yields were eroded and positive cash flow in property investments disappeared as house values climbed faster than rents. Then that trend reversed and yields slowly began improving”, according to two The New Zealand Herald reporters writing in May 2009.[118] In the middle of 2009, house prices had dropped, interest rates were low, and buy-to-let property investment was again looking attractive, particularly in the Lambton precinct, according to these two reporters.[118]

Current

[edit]

Since 2009, house prices in Wellington have increased significantly. In May 2021, the Real Estate Institute of New Zealand (REINZ) reported the median house price was $1,057,000 in Wellington City, $930,000 in Porirua, $873,500 in Lower Hutt and $828,000 in Upper Hutt, compared to a national median house price of $820,000.[119] The substantial increase in house prices has made it difficult for first home buyers to purchase a home in the city and is also credited with pushing up the house prices in neighbouring cities like Porirua.[120] Wellington house prices peaked in February 2022, and by December 2023 had fallen by 25%.[121]

Housing costs have been identified making it difficult for some professions, like nurses, to afford to live in Wellington.[122][123] The median rent in Wellington has also increased significantly in recent years to $600 per week, higher even than Auckland.[124]

Housing quality

[edit]

Despite the high cost of housing in the capital, the quality of housing in Wellington has been criticised as being poor. 18.4% of houses in Wellington City are sometimes or always mouldy and 24% are sometimes or always damp.[125] Both of these are higher than the New Zealand average.

Demographics

[edit]

A Wellington City Council survey conducted in March 2009 found the typical central city apartment dweller was a New Zealand native aged 24 to 35 with a professional job in the downtown area, with household income higher than surrounding areas.[126] Three-quarters (73%) walked to work or university, 13% travelled by car, 6% by bus, 2% bicycled (although 31% own bicycles), and did not travel very far since 73% worked or studied in the central city.[126] The large majority (88%) did not have children in their apartments; 39% were couples without children; 32% were single-person households; 15% were groups of people flatting together.[126] Most (56%) owned their apartment; 42% rented.[126] The report continued: “The four most important reasons for living in an apartment were given as lifestyle and city living (23%), close to work (20%), close to shops and cafes (11%) and low maintenance (11%) … City noise and noise from neighbours were the main turnoffs for apartment dwellers (27%), followed by a lack of outdoor space (17%), living close to neighbours (9%) and apartment size and a lack of storage space (8%).”[126][127]

Households are primarily one-family, making up 66.9% of households, followed by single-person households (24.7%); there were fewer multiperson households and even fewer households containing two or more families. These counts are from the 2013 census for the Wellington region (which includes the surrounding area in addition to the four cities).[128]

Economy

[edit]

Wellington Harbour ranks as one of New Zealand’s chief seaports and serves both domestic and international shipping. The port handles approximately 10.5 million tonnes of cargo on an annual basis,[129] importing petroleum products, motor vehicles, minerals and exporting meats, wood products, dairy products, wool, and fruit. Many cruise ships also use the port.

The Government sector has long been a mainstay of the economy, which has typically risen and fallen with it. Traditionally, its central location meant it was the location of many head offices of various sectors – particularly finance, technology and heavy industry – many of which have since relocated to Auckland following economic deregulation and privatisation.[130][131]

In recent years, tourism, arts and culture, film, and ICT have played a bigger role in the economy. Wellington’s median income is well above the average in New Zealand,[132] and the highest of all New Zealand cities.[133] It has a much higher proportion of people with tertiary qualifications than the national average.[134] Major companies with their headquarters in Wellington include:

- Centreport

- Chorus Networks

- Contact Energy

- The Cooperative Bank

- Datacom Group

- Infratil

- Kiwibank

- Meridian Energy

- NZ Post

- NZX

- Todd Corporation

- Trade Me

- Weta Digital

- Wellington International Airport

- Xero

- Z Energy

At the 2013 census, the largest employment industries for Wellington residents were professional, scientific and technical services (25,836 people), public administration and safety (24,336 people), health care and social assistance (17,446 people), education and training (16,550 people) and retail trade (16,203 people).[135] In addition, Wellington is an important centre of the New Zealand film and theatre industry, and second to Auckland in terms of numbers of screen industry businesses.[136]

Tourism

[edit]

See also: Tourism in New Zealand

Tourism is a major contributor to the city’s economy, injecting approximately NZ$1.3 billion into the region annually and accounting for 9% of total FTE employment.[137] The city is consistently named as New Zealanders’ favourite destination in the quarterly FlyBuys Colmar Brunton Mood of the Traveller survey[138] and it was ranked fourth in Lonely Planet Best in Travel 2011’s Top 10 Cities to Visit in 2011.[139] New Zealanders make up the largest visitor market, with 3.6 million visits each year; New Zealand visitors spend on average NZ$2.4 million a day.[140] There are approximately 540,000 international visitors each year, who spend 3.7 million nights and NZ$436 million. The largest international visitor market is Australia, with over 210,000 visitors, spending approximately NZ$334 million annually.[141] It has been argued that the construction of the Te Papa museum helped transform Wellington into a tourist destination.[142] Wellington is marketed as the ‘coolest little capital in the world’ by Positively Wellington Tourism, an award-winning regional tourism organisation[143] set up as a council controlled organisation by Wellington City Council in 1997.[144] The organisation’s council funding comes through the Downtown Levy commercial rate.[145] In the decade to 2010, the city saw growth of over 60% in commercial guest nights. It has been promoted through a variety of campaigns and taglines, starting with the iconic Absolutely Positively Wellington advertisements.[146] The long-term domestic marketing strategy was a finalist in the 2011 CAANZ Media Awards.[147]

Popular tourist attractions include Wellington Museum, Wellington Zoo, Zealandia and Wellington Cable Car. Cruise tourism is experiencing a major boom in line with nationwide development. The 2010/11 season saw 125,000 passengers and crew visits on 60 liners. There were 80 vessels booked for visits in the 2011/12 season – estimated to inject more than NZ$31 million into the economy and representing a 74% increase in the space of two years.[148]

Wellington is a popular conference tourism destination due to its compact nature, cultural attractions, award-winning restaurants and access to government agencies. In the year ending March 2011, there were 6,495 conference events involving nearly 800,000 delegate days; this injected approximately NZ$100 million into the economy.[149]

Arts and culture

[edit]

Culture

[edit]

Owing to the work of Positively Wellington Tourism in marketing it as “the coolest little capital”,[143] the city has been injected into the global zeitgeist as exactly that.[150] It has been traditionally acclaimed as New Zealand’s “cultural and creative capital”.[151][152][153] The city is known for its coffee scene, with now-globally common foods and drinks such as the flat white perfected here.[154][155] Wellington has a strong coffee culture – the city has more cafés per capita than New York City – and was pioneered by Italian and Greek immigrants to areas such as Mount Victoria, Island Bay and Miramar.[156] Nascent influence is derived from Ethiopian migrants. Wellington’s cultural vibrance and diversity is well known across the world. It is New Zealand’s second most ethnically diverse city, bested only by Auckland, and boasts a “melting pot” culture of significant minorities such as Malaysian,[157] Italian, Dutch, Korean, Chinese, Greek,[158] Indian, Samoan and indigenous Taranaki Whānui communities as a result. In particular, Wellington is noted for is contributions to art, cuisine[159] and international filmmaking (with Avatar and The Lord of the Rings being largely produced in the city) among many other factors listed below. The World of Wearable Arts (WOW) is an annual event that brings lots of visitors to Wellington every year.[160]

Museums and cultural institutions

[edit]

Wellington is home to many cultural institutions, including Te Papa (the Museum of New Zealand), the National Library of New Zealand, Archives New Zealand, Wellington Museum (formerly the Wellington Museum of City and Sea), the Katherine Mansfield House and Garden (formerly Katherine Mansfield Birthplace), Colonial Cottage, the Wellington Cable Car Museum, the Reserve Bank Museum, Old St Paul’s, the National War Memorial[21] Ngā Taonga Sound and Vision, Capital E children’s playspace and the Wellington City Gallery.

Festivals

[edit]

Wellington is home to many high-profile events and cultural celebrations, including the biennial New Zealand Festival of the Arts, biennial Wellington Jazz Festival, biennial Capital E National Arts Festival for Children and major events such as World of Wearable Art, TEDxWellington, Cuba Street Carnival, Wellington On a Plate, New Zealand Fringe Festival, New Zealand International Comedy Festival, New Zealand Affordable Art Show, Out In The Square, Beervana, and Homegrown Music Festival.

The annual children’s Artsplash Festival brings together hundreds of students from across the region. The week-long festival includes music and dance performances and the presentation of visual arts.[161] The Performance Arcade is an annual live-art event in shipping containers on the waterfront.[162]

Film

[edit]

Filmmakers Sir Peter Jackson, Sir Richard Taylor and a growing team of creative professionals have turned the eastern suburb of Miramar into a film-making, post-production and special effects infrastructure centre, giving rise to the moniker ‘Wellywood‘.[163][164] Jackson’s companies include Wētā Workshop, Wētā FX, Camperdown Studios, post-production house Park Road Post, and Stone Street Studios near Wellington Airport.[165][166] Films shot partly or wholly in Wellington include the Lord of The Rings trilogy, King Kong and Avatar. Jackson described Wellington: “Well, it’s windy. But it’s actually a lovely place, where you’re pretty much surrounded by water and the bay. The city itself is quite small, but the surrounding areas are very reminiscent of the hills up in northern California, like Marin County near San Francisco and the Bay Area climate and some of the architecture. Kind of a cross between that and Hawaii.”[167]

Sometime Wellington directors Jane Campion and Geoff Murphy have reached the world’s screens with their independent spirit. Emerging Kiwi filmmakers, like Robert Sarkies, Taika Waititi, Costa Botes and Jennifer Bush-Daumec,[168] are extending the Wellington-based lineage and cinematic scope. There are agencies to assist film-makers with tasks such as securing permits and scouting locations.[169]

Wellington has a large number of independent cinemas, including the Embassy Theatre, Penthouse, the Roxy and Light House, which participate in film festivals throughout the year. Wellington has one of the country’s highest turn-outs for the annual New Zealand International Film Festival. There are a number of other film festivals hosted in Wellington, such as Doc Edge (documentary),[170] the Japanese Film Festival[171] and Show Me Shorts (short films).[172]

Music

[edit]

The music scene has produced bands such as The Warratahs, The Mockers, The Phoenix Foundation, Shihad, Beastwars, Fly My Pretties, Rhian Sheehan, Birchville Cat Motel, Black Boned Angel, Fat Freddy’s Drop, The Black Seeds, Fur Patrol, Flight of the Conchords, Connan Mockasin, Rhombus and Module, Weta, Demoniac, and DARTZ. The New Zealand School of Music was established in 2005 through a merger of the conservatory and theory programmes at Massey University and Victoria University of Wellington. New Zealand Symphony Orchestra, Nevine String Quartet and Chamber music New Zealand are based in Wellington. The city is also home to the Rodger Fox Big Band.

Theatre and dance

[edit]

Wellington is home to BATS Theatre, Circa Theatre, the national kaupapa Māori theatre company Taki Rua, the National Theatre for Children at Capital E, the Royal New Zealand Ballet, Gryphon Theatre, and contemporary dance company Footnote.

Venues include St James’ Theatre on Courtenay Place,[173] The Opera House on Manners Street and the Hannah Playhouse.

Te Whaea National Dance & Drama Centre, houses New Zealand’s university-level schools, Toi Whakaari: New Zealand Drama School & the New Zealand School of Dance, these are separate entities that share the building’s facilities.

Te Auaha the Whitireia Performing Arts Centre is downtown off Cuba Street.

St James Theatre on Courtenay Place, the main street of Wellington’s entertainment district

Comedy

[edit]

Many of New Zealand’s prominent comedians have either come from Wellington or got their start there, such as Ginette McDonald (“Lyn of Tawa”), Raybon Kan, Dai Henwood, Ben Hurley, Steve Wrigley, Guy Williams, the Flight of the Conchords and the satirist John Clarke (“Fred Dagg“).

Wellington is home to groups that perform improvised theatre and improvisational comedy, including Wellington Improvisation Troupe (WIT).[citation needed] The comedy group Breaking the 5th Wall[174] operated out of Wellington and regularly did shows around the city, performing a mix of sketch comedy and semi-improvised theatre. In 2012, the group disbanded when some of its members moved to Australia.

Wellington hosts shows in the annual New Zealand International Comedy Festival.[175]

Visual arts

[edit]

From 1936 to 1992, Wellington was home to the National Art Gallery of New Zealand, when it was amalgamated into Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. Wellington is home to the New Zealand Academy of Fine Arts and the Arts Foundation of New Zealand. The city’s arts centre, Toi Pōneke, is a nexus of creative projects, collaborations, and multi-disciplinary production. Arts Programmes and Services Manager Eric Vaughn Holowacz and a small team based in the Abel Smith Street facility have produced ambitious initiatives such as Opening Notes, Drive by Art, and public art projects. The city is home to the experimental arts publication White Fungus. The Learning Connexion provides art classes. Other visual art galleries include the City Gallery.

- Te Ngākau Civic Square with the Ferns artwork suspended above

Cuisine

[edit]

Wellington is characterised by small dining establishments, and its café culture is internationally recognised, being known for its large number of coffeehouses.[176][177] There are a few iconic cafés that started the obsession with coffee that Wellington has. One of these is the Deluxe Expresso Bar that opened in 1988.[178] Wellington Restaurants offer cuisines including from Europe, Asia and Polynesia; for dishes that have a distinctly New Zealand style, there are lamb, beef, pork and venison, salmon, crayfish (lobster), Bluff oysters, pāua (abalone), mussels, scallops, pipis and tuatua (both New Zealand shellfish); kūmara (sweet potato); kiwifruit and tamarillo; and pavlova, the national dessert.[179]

Sport

[edit]

Wellington is the home to:

- Hurricanes – Super Rugby team based in Wellington

- Wellington Lions – ITM Cup rugby team

- Wellington Phoenix FC – football (soccer) club playing in the Australasian A-League, the only fully professional football club in New Zealand

- Team Wellington – in the semi-professional New Zealand Football Championship

- Central Pulse – netball team representing the Lower North Island in the ANZ Championship, primarily based in Wellington

- Wellington Firebirds and Wellington Blaze – men’s and women’s cricket teams

- Wellington Saints – basketball team in the National Basketball League

Government

[edit]

Local

[edit]

Wellington city is administered by the territorial authority of Wellington City Council. The present mayor of the Wellington City Council is Tory Whanau, who was elected in 2022.

Wellington is also part of the wider Wellington Region, administered by the Greater Wellington Region Council. The local authorities are responsible for a wide variety of public services, which include management and maintenance of local roads, and land-use planning.[180]

Community boards

[edit]

The Wellington City Council has created two local community boards under the provisions of Part 4 of the Local Government Act 2002[181] for certain parts of the city:

- The Tawa Community Board[3] representing the northern suburbs of Tawa, Grenada North and Takapū Valley;[1] and

- The Mākara/Ōhāriu Community Board[4] representing the rural suburbs of Ohariu, Mākara and Mākara Beach.[1]

National

[edit]

Wellington is covered by four general electorates: Mana, Ōhāriu, Rongotai, and Wellington Central. It is also covered by two Māori electorates: Te Tai Hauāuru, and Te Tai Tonga. Each electorate returns one member to the New Zealand House of Representatives. Two general electorates are held by the Labour Party and two are held by the Green Party and the two Maori electorates are held by Te Pāti Māori.

In addition, there are a number of Wellington-based list MPs, who are elected via party lists.

Due to Wellington being the capital city of New Zealand, its residents are more likely to participate in politics compared to other cities in New Zealand.[21]

Education

[edit]

Main article: List of schools in the Wellington Region

See also: List of universities in New Zealand

Wellington offers a variety of college and university programs for tertiary students:

Victoria University of Wellington has four campuses and works with a three-trimester system (beginning March, July, and November).[182] It enrolled 21,380 students in 2008; of these, 16,609 were full-time students. Of all students, 56% were female and 44% male. While the student body was primarily New Zealanders of European descent, 1,713 were Māori, 1,024 were Pacific students, 2,765 were international students. 5,751 degrees, diplomas and certificates were awarded. The university has 1,930 full-time employees.[183]

Massey University has a Wellington campus known as the “creative campus” and offers courses in communication and business, engineering and technology, health and well-being, and creative arts. Its school of design was established in 1886 and has research centres for studying public health, sleep, Māori health, small & medium enterprises, disasters, and tertiary teaching excellence.[184] It combined with Victoria University to create the New Zealand School of Music.[184]

The University of Otago has a Wellington branch, with its Wellington School of Medicine and Health.

Whitireia New Zealand has large campuses in Porirua, Wellington and Kapiti; the Wellington Institute of Technology and New Zealand’s National Drama school, Toi Whakaari. The Wellington area has numerous primary and secondary schools.

Transport

[edit]

See also: Public transport in the Wellington Region and List of bus routes in the Wellington Region

Wellington is served by State Highway 1 in the west and State Highway 2 in the east, meeting at the Ngauranga Interchange north of the city centre, where SH 1 runs through the city to the airport. There are two other state highways in the wider region: State Highway 58 which provides a direct connection between the Hutt Valley and Porirua, and State Highway 59 which follows a coastal route between Linden and Mackays Crossing and was previously part of SH 1.[186][187] Road access into the capital is constrained by the mountainous terrain – between Wellington and the Kāpiti Coast, SH 1 passes through the steep and narrow Wainui Saddle, nearby SH 59 travels along the Centennial Highway, a narrow section of road between the Paekākāriki Escarpment and the Tasman Sea, and between Wellington and Wairarapa SH 2 transverses the Rimutaka Ranges on a similar narrow winding road. Wellington has two motorways: the Johnsonville–Porirua Motorway (largely part of SH 1, with the northernmost section part of SH 59) and the Wellington Urban Motorway (entirely part of SH 1), which in combination with a small non-motorway section in the Ngauranga Gorge connect Porirua with Wellington city. A third motorway in the wider region, the Transmission Gully Motorway forming part of the SH 1 route and officially opened on 30 March 2022, leaves the Johnsonville-Porirua Motorway at the boundary between Wellington and Porirua and provides the main route between Wellington and the wider North Island.[188]

Bus transport in Wellington is supplied by several different operators under the banner of Metlink. Buses serve almost every part of Wellington city, with most of them running along the “Golden Mile” from Wellington railway station to Courtenay Place. Until October 2017, there were nine trolleybus routes, all other buses running on diesel. The trolleybus network was the last public system of its kind in the Southern Hemisphere.[189]

Wellington lies at the southern end of the North Island Main Trunk railway (NIMT) and the Wairarapa Line, converging on Wellington railway station at the northern end of central Wellington. Two long-distance services leave from Wellington: the Capital Connection, for commuters from Palmerston North, and the Northern Explorer to Auckland.

Four electrified suburban lines radiate from Wellington railway station to the outer suburbs to the north of Wellington – the Johnsonville Line through the hillside suburbs north of central Wellington; the Kapiti Line along the NIMT to Waikanae on the Kāpiti Coast via Porirua and Paraparaumu; the Melling Line to Lower Hutt via Petone; and the Hutt Valley Line along the Wairarapa Line via Waterloo and Taitā to Upper Hutt. A diesel-hauled carriage service, the Wairarapa Connection, connects several times daily to Masterton in the Wairarapa via the 8.8-kilometre-long (5.5 mi) Rimutaka Tunnel. Combined, these five services carry 11.64 million passengers per year.[190] CentrePort Wellington is the operator of the port of Wellington, and provides infrastructure for shipping and cargo, including the commercial wharves in Wellington Harbour. It also provides port services for the Cook Strait ferries to Picton in the South Island, operated by state-owned Interislander and private Bluebridge. Local ferries connect Wellington city centre with Eastbourne and Seatoun.[191]

Wellington International Airport is 6 kilometres (3.7 mi) south-east of the city centre. It is serviced by flights from across New Zealand, Australia, Singapore (via Melbourne), and Fiji. Flights to other international destinations require a transfer at another airport, as aircraft range is limited by Wellington’s short (2,081-metre or 6,827-foot) runway, which has become an issue in recent years regarding the Wellington region’s economic performance.[192][193]

Infrastructure

[edit]

Electric power

[edit]

Wellington’s first public electricity supply was established in 1904, alongside the introduction of electric trams, and was originally supplied at 105 volts 80 hertz. The conversion to the now-standard 230/400 volts 50 hertz began in 1925, the same year the city was connected to the Mangahao hydroelectric scheme. Between 1924 and 1968, the city’s supply was supplemented by a coal-fired power station at Evans Bay.[194]

Today, Wellington city is supplied from four Transpower substations: Takapu Road, Kaiwharawhara, Wilton, and Central Park (Mount Cook). Wellington Electricity owns and operates the local distribution network.

The city is home to two large wind farms, West Wind and Mill Creek, which combined contribute up to 213 MW of electricity to the city and the national grid.

While Wellington experiences regular strong winds, and only 63% of Wellington Electricity’s network is underground, the city has a very reliable power supply. In the year to March 2018, Wellington Electricity disclosed the average customer spent just 55 minutes without power due to unplanned outages.[195]

Natural gas

[edit]

Wellington was one of the original nine towns and cities in New Zealand to be supplied with natural gas when the Kapuni gas field entered production in 1970, and a 260-kilometre-long (160 mi) high-pressure pipeline from the field in Taranaki to the city was completed. The high-pressure transmission pipelines supplying Wellington are now owned and operated by First Gas, with Powerco owning and operating the medium- and low-pressure distribution pipelines within the urban area.[196]

The three waters

[edit]

Main article: Water supply and sanitation in the Wellington region

The “three waters” – drinking water, stormwater, and wastewater services for the Wellington metropolitan area are provided by five councils: Wellington City, Hutt, Upper Hutt and Porirua city councils, and the Greater Wellington Regional Council. However, the water assets of these councils are managed by an infrastructure asset management company, Wellington Water.

Wellington’s first piped water supply came from a spring in 1867.[197] Greater Wellington Regional Council now supplies Lower Hutt, Porirua, Upper Hutt and Wellington with up to 220 million litres a day.[198] The water comes from Wainuiomata River (since 1884), Hutt River (1914), Ōrongorongo River (1926) and the Waiwhetū Aquifer.[199]

There are four wastewater treatment stations serving the Wellington metropolitan area, located at:[200]

- Moa Point (serving Wellington city)

- Seaview (serving Lower Hutt and Upper Hutt)

- Karori (serving the suburb)

- Porirua (serving northern Wellington suburbs, Tawa and Porirua city)

The Wellington metropolitan area faces challenges with ageing infrastructure for the three waters, and there have been some significant failures, particularly in wastewater systems. The water supply is vulnerable to severe disruption during a major earthquake, although a wide range of projects are planned to improve the resilience of the water supply and allow a limited water supply post-earthquake.[201][202]

In May 2021, the Wellington City Council approved a 10-year plan that included expenditure of $2.7 billion on water pipe maintenance and upgrades in Wellington city, and an additional $147 to $208 million for plant upgrades at the Moa Point wastewater treatment plant.[203] In November 2023, Wellington Water noted that on-going investment of $1 billion per annum was required to address water issues across the Greater Wellington region, but that this amount was beyond the funding capacity of councils.[204]

Media

[edit]

Newspapers

[edit]

For many years Wellington had two daily newspapers – The Evening Post in the afternoon and The Dominion in the morning. The Evening Post was founded in 1865 by Dublin-born printer, newspaper manager and leader-writer Henry Blundell,[205] while The Dominion was first published on 26 September 1907, the day New Zealand achieved Dominion status.[206] The two newspapers merged in 2002 to form The Dominion Post[207] and in April 2023 the merged newspaper was renamed The Post.[208]

Radio

[edit]

Wellington is served by 26 full-power radio stations: 17 on FM, four on AM, and five on both FM and AM.

Television

[edit]

Television broadcasts began in Wellington on 1 July 1961 with the launch of channel WNTV1, becoming the third New Zealand city (after Auckland and Christchurch) to receive regular television broadcasts. WNTV1’s main studios were in Waring Taylor Street in central Wellington and broadcast from a transmitter atop Mount Victoria. In 1967, the Mount Victoria transmitter was replaced with a more powerful transmitter at Mount Kaukau.[209] In November 1969, WNTV1 was networked with its counterpart stations in Auckland, Christchurch and Dunedin to form NZBC TV.

In 1975, the NZBC was broken up, with Wellington and Dunedin studios taking over NZBC TV as Television One while Auckland and Christchurch studios launched Television Two. At the same time, the Wellington studios moved to the new purpose-built Avalon Television Centre in Lower Hutt. In 1980, Televisions One and Two merged under a single company, Television New Zealand (TVNZ). The majority of television production moved to Auckland over the 1980s, culminating in the opening of TVNZ’s new Auckland television centre in 1989.

Today, digital terrestrial television (Freeview) is available in the city, transmitting from Mount Kaukau plus three infill transmitters at Baxters Knob, Fitzherbert, and Haywards.[210]

Sister cities

[edit]

Wellington has sister city relationships with the following cities:[211]

- Sydney, Australia (1983)

- Xiamen, China (1987)

- Sakai, Japan (1994)

- Beijing, China (2006)

- Canberra, Australia (2016)

Wellington is also a “friendly city” with Ramallah, Palestine, and a 2023 council vote means both are expected to be sister cities in the future.[212][213] Wellington also has historical ties with Chania, Greece; Harrogate, England; and Çanakkale, Turkey.[214]

Wellington metropolitan area

[edit]

The wider metropolitan area for Wellington encompasses areas administered by four local authorities: Wellington City itself, on the peninsula between Cook Strait and Wellington Harbour; Porirua City on Porirua Harbour to the north, notable for its large Māori and Pasifika communities; and Lower Hutt City and Upper Hutt City, largely suburban areas to the northeast, together known as the Hutt Valley. Depending on the source, the Wellington metro area may include Waikanae, Paraparaumu and Paekākāriki on the Kāpiti Coast, and/or Featherston and Greytown in the Wairarapa.

The urban areas of the four local authorities have a combined population of 434,300 residents as of June 2024.[9]

The four cities comprising the Wellington metropolitan area have a total population of 440,700 (June 2024),[9] with the urban area containing 98.5% of that population. The remaining areas are largely mountainous and sparsely farmed or parkland and are outside the urban area boundary. More than most cities, life is dominated by its central business district (CBD). Approximately 62,000 people work in the CBD, only 4,000 fewer than work in Auckland’s CBD, despite that city having four times the population.

The Waikanae–Paraparaumu–Paekākāriki combined urban area in the Kāpiti Coast district is sometimes included in the Wellington metro area[by whom?] due to its exurban nature and strong transport links with Wellington. If included as part of the Wellington metro, Waikanae-Paraparaumu-Paekākāriki would add 45,250 to the population (as of June 2024).[9]

Featherston and Greytown in the Wairarapa are rarely considered part of the Wellington metropolitan area, being physically separated from the rest of the metropolitan area by the Remutaka Range. However, both have significant proportions of their employed population working in Wellington city and the Hutt Valley (36.1% and 17.1% in 2006 respectively)[215] and are considered part of the Wellington functional urban area by Statistics New Zealand.[216]

The four urban areas combined had a usual resident population of 401,850 at the 2018 New Zealand census, an increase of 26,307 people (7.0%) since the 2013 census, and an increase of 42,726 people (11.9%) since the 2006 census. There were 196,911 males and 204,936 females, giving a sex ratio of 0.961 males per female. Of the total population, 74,892 people (18.6%) were aged up to 15 years, 93,966 (23.4%) were 15 to 29, 185,052 (46.1%) were 30 to 64, and 47,952 (11.9%) were 65 or older.